Portfolio update 6 July 2025

Weekly news and trading intentions featuring LON:OCDO, LON:MERC, LON:ACSO

Please bear in mind when reading this post that I own shares in the stocks mentioned, which likely distorts my perspective. Also, the following content represents my personal views only and is not investment advice. Please see the about page for my disclosure policy.

The UK investing portfolio, UK trading portfolio and Australian portfolio pages are all up to date as at COB on Friday.

There was no significant news for any of the stocks in my investing portfolio this week. I’ve taken a closer look at a few stocks over the past couple of weeks and discuss three of these below.

I have held Mercia Asset Management (LON:MERC) shares in my trading portfolio for a while and recently did a bit of research to determine whether I would buy it for my investing portfolio. Currently, I would not.

The stock is cheap. It trades at slightly less than its tangible assets, but Mercia is increasingly a manager of third party assets rather than a listed investment vehicle. Funds management generated £7.6 million of EBITDA in 2025, although this excludes share based payments of £940k. This compares to a market cap of £142 million. The company’s owned investment portfolio is being wound down, with the proceeds to be used for shareholder returns, acquisitions and seeding new funds.

Mercia is focused on UK private assets. It has a number of regional offices which provide it with access to deals outside of the South East. The company claims this gives it an edge over London centred peers, but I don’t see why it would be difficult for others to replicate, even if it would take some time.

Mercia has a longstanding relationship with British Business Bank which is the recipient of funds under the government’s recently announced industrial strategy. The Mansion House Accord promises more domestic pension money for UK private assets. Mercia is a beneficiary of these trends.

I think the stock will perform well in the short-medium term and I have no intention of selling. However, what holds me back from adding it to my investing portfolio is that fund management is a fickle business. Right now, growth in private markets is lifting all boats. This may continue for some years, but at some point the industry will mature, fees will get squeezed and the weaker players will be weeded out.

Mercia currently earns a blended fee margin of 2%. Management expects this to fall as it expands into real assets which do not command as high fees as its venture arm. Its funds are closed ended which protects its fee structure. However, this doesn’t mean that they can’t be wound down or, in the case of its venture capital trusts, that the government could take away tax breaks. In any case, attracting future funds relies on past performance.

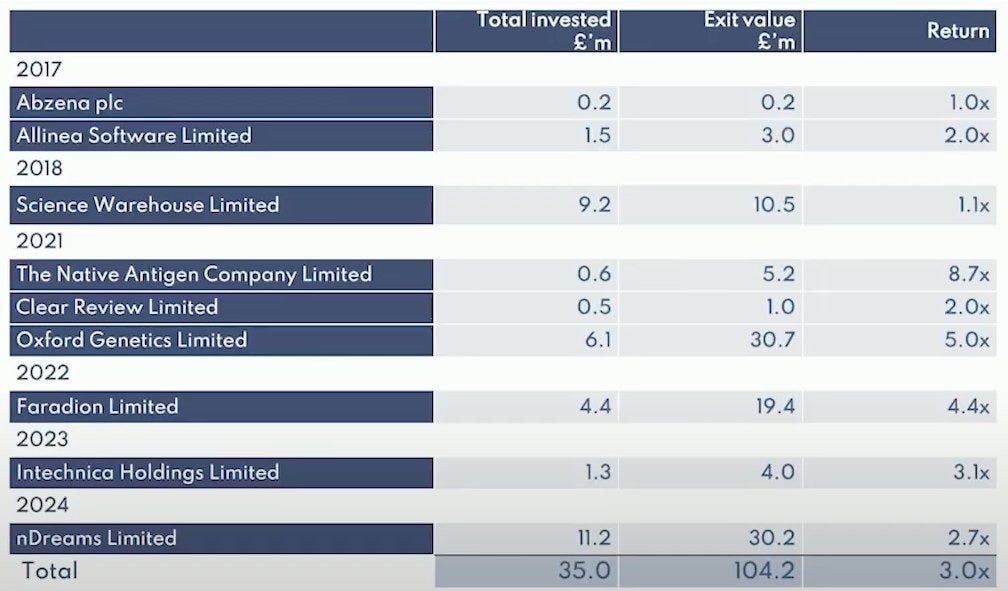

I don’t really know how well Mercia’s various funds perform on average as there is little publicly available data. However, I did find it interesting that of the nine balance sheet investments that it has exited to date, there are no huge winners. The remaining portfolio contains no outsized positions either. My understanding of the venture industry is that a small number of extreme performers drive all of the overall returns.

Source: Mercia investor presentation

Even if Mercia’s funds do deliver sustainable outperformance, this might still depend on a small number of key decision makers who could leave.

The Mercia Nucleus is an extensive network of non-execs which might represent a sustainable competitive advantage, but I imagine that most venture managers have similar networks.

My failure to uncover a sustainable source of edge in Mercia’s business prevents me from holding the company long-term. I am not saying that it doesn’t exist, just that I cannot see it at the moment (perhaps it is not something which is visible to outside observers). I will keep looking, and in the meantime I am glad to have some exposure given the group is attracting inflows into its profitable fund management business, and this is not reflected in the share price.

I think that Accesso Technology Group (LON:ACSO) is a high quality company that is an attractive takeover target, possibly for its largest shareholder, Long Path Partners. I own a very small position across a couple of undisclosed accounts that I manage in the same way as my investing portfolio.

According to its website, “Long Path Partners is a privately-owned investment firm that seeks to compound capital by investing in a limited number of high quality, predictable businesses that we intend to own for the long term.”

Long Path has been increasing its stake in Accesso recently and now holds 18% of the company. It has just had one of its partners, Brian Nelson, appointed to the Accesso board.

Accesso provides various software products to theme parks and other attractions which help run ticketing, queuing and restaurant & retail offerings. The vast majority of revenue is repeating (tied to customer revenue) and just under two thirds is derived from the US.

Accesso is a recurring revenue software company providing mission critical systems to a niche market. It isn’t growing that fast currently (5% revenue, 7% gross profit CAGR over the past five years), but I still think that it is too cheap given it trades on a price-to-sales ratio of less than 2. There is also roughly 10% of the company’s market cap in net cash.

Source: ShareScope

Last year was tough for US theme parks with visitor numbers disappointing and I think this partially explains Accesso’s inexpensive share price. At some point, the cycle will turn and operating leverage will kick in, which reminds me:

One theme I have been thinking about recently is companies which can use AI to reduce costs without an impact on revenue. I think that software companies which are deeply embedded into their customers’ businesses fit this description. Indeed, CEO Stephen Brown said the following in the latest annual report:

“In terms of gaining operational efficiency, our engineering teams are implementing AI tooling where applicable to increase output and accelerate innovation.”

Accesso modestly reduced its headcount last year and is seeing improving margins. Despite this, it does not seem that the company under-appreciates its employees given voluntary staff turnover is just 5% — another indicator of quality.

Accesso generates more cash than profit which is an attractive feature. This is because it amortises intangibles related to acquisitions and does not capitalise much product development. In addition, share based payments are high and were $3.7 million last year which is less desirable from a shareholder perspective, but could potentially be eliminated by an acquirer.

The resilient nature of Accesso’s revenues combined with its strong cash generation make it a suitable leveraged buyout candidate. Perhaps Long Path's recent share purchases reflect this or maybe they were just a precursor to getting a seat on the board. Long Path has taken a listed company private previously when it acquired French media company, Dalet, back in 2020.

Regardless of whether Accesso is bought out, I think there is untapped value here. Aside from a possible cyclical recovery and continued margin expansion, Long Path might use its board seat to agitate for capital returns (Accesso does not currently pay a dividend).

I am comfortable investing alongside a long-term quality based fund like Long Path. There is always the risk with a dominant major shareholder that they look to opportunistically squeeze out minority holders during a bout of market depression. However, I think that I have bought at a sufficiently low price to mitigate this possibility and besides, this is an established profitable company, not some marginal basket case.

I need to do more research here, particularly regarding Accesso’s product suite and leadership team before I would consider acquiring a significant position. I could easily have missed something crucial.

Earlier this week, I bought an even smaller position than my Accesso holding in Ocado Group (LON:OCDO), also held within an undisclosed account.

Ocado is down more than 90% since it reached all-time highs in the post covid boom. The group consists of three interrelated businesses.

Firstly, there is Ocado Retail, which was the original business and is an online supermarket. Since 2019, it has been 50% owned by Marks & Spencer which paid up to £750 million for its share. £560 million of this was an upfront payment and there is an ongoing dispute over the remaining £190 million.

When M&S got involved, Ocado Retail had revenue of about £1.5 billion. Today, it has revenue approaching £3 billion so it might be reasonable to assume that the valuation of Ocado’s share has also doubled to around £1.5 billion. The business is modestly profitable with EBITDA margin expansion forecast this year.

Premium positioning, mid-teens revenue growth and high customer satisfaction support a 1x revenue valuation in my view. M&S trades on 0.5x sales and Tesco trades on a ratio of less than 0.4, but they are only growing at mid single digits in percentage terms.

Ocado Logistics is the second business. It has two customers being Morrisons and Ocado Retail. Ocado Logistics manages automated warehouses and last mile delivery for these customers. It is a cost plus business which reliably makes around £30 million in EBITDA.

Ocado Logistics grows at a slower rate than its customers because the automated warehouses it runs are getting more efficient over time. The subsidiary increased sales by 7.6% in 2024. I reckon that this business might be worth around £200 million representing a 7x EBITDA multiple. Clearly there is customer concentration risk, but the warehouses which it operates are run on Ocado’s technology and switching to a third party would be risky.

So between these two businesses I think there is £1.7 billion of value. Ocado’s market cap is £2 billion. Group net debt excluding lease liabilities is £700 million to give an enterprise value of £2.7 billion. Taking off my estimated values for the retail and logistics arms gives £1 billion of unaccounted for market value.

The final division is Ocado Technology and it is the reason that at one time Ocado’s market cap was about £20 billion. Ocado technology designs and makes the software and robotics that are used in the automated warehouses, called customer fulfilment centres (CFCs), of its customers.

Unsurprisingly, Ocado Retail is a customer and contributes around £150 million in annualised revenue. Morrisons is another, and has been since 2013. From 2017, Ocado has sold its advanced wares overseas and now has 13 partners in total.

The economics of the technology division are more attractive than the other two. The business invests in material handling equipment (MHE - basically robots) which it leases to customers and earns recurring license revenue on its internally developed software. Contracts also include upfront fees and Ocado reckons it can earn 40% ROCE at the CFC level from its latest technology.

Gross margins are strong and improving: currently 70% and rising to 75% in the near term. And management is promising positive cash flow generation by FY27 after covering hefty capitalised development costs running at about £200 million per year. I think that this is likely to be achieved given strong recent progress including a reduction in outflows by £249 million to £224 million on an underlying basis in FY24.

Source: Ocado FY24 results presentation

The technology is impressive. For example, Ocado created its own communication protocol to handle the noise and speed requirements of the thousands of robots within its CFCs. It also designs its own ultra-lightweight robots to maximise efficiency, which it reckons work four times as hard as those of its nearest competitor.

So far so good, and it is easy to see how the market got excited by Ocado in the liquidity drenched year of 2021. However, there are also sound reasons why the market no longer ascribes much value to the tech division.

Ocado Technology generated £500 million of revenue in 2024, much of it recurring. Therefore, my figure of £1 billion in residual market value from earlier represents just two times sales. That revenue is generated from about 25 CFCs and Ocado reckons that there could ultimately be hundreds of them across the world — clearly, the market disagrees.

In recent years, partners have slowed the roll-out of CFCs. Most notably, US grocer Kroger intended to build 20 CFCs at the inception of its partnership in 2018, but only 8 of these are currently live. The initial plan was for all 20 to be rolled out in three years and Kroger is currently reviewing its e-commerce business, admitting that it is not yet profitable.

There are similar stories elsewhere. In Canada, Sobeys has paused future CFCs and given up exclusivity. Morrisons also recently stopped using Ocado’s Erith site, in part reverting to in-store fulfilment.

In 2024, Ocado Retail paid £33.2 million in fees for a CFC in Hatfield despite the fact it ceased operations in 2023. Partners are tied into long-term leases which might mean that customers continue to run sites even if it is not economical to do so. This makes it hard to assess the quality of the technology division.

One reason that roll-outs have slowed is because of the post covid normalisation in online shopping. It has been a difficult period to forecast future demand and perhaps that is now changing with the return of more consistent growth. Another reason is that rising interest rates have raised the return hurdle for a partner to make a CFC investment.

Source: Ocado FY24 results presentation

However, I think there is more than this going on. I’m unconvinced that the economics of CFCs currently work for partners and this may or may not be due to the immaturity of the online delivery market. In other words, perhaps these are just development pains, but if not then the entire model might be flawed.

Here is the problem as I see it. Mass market supermarket retailers make low gross margins, say 25% to 30%. Last mile delivery costs around 15% to 20% of revenue and Ocado Technology has a roughly 5% take rate. This doesn’t leave much room for other operating costs and profit.

Traditional grocers have extensive store networks which are costly to run and they generate tiny net margins of a couple of per cent. Under Ocado’s solution they need to create a parallel infrastructure requiring substantial capital expense and taking years to reach scale and profitability. Even then, supermarkets would likely have to charge higher prices for online delivery compared to stores to cover delivery costs.

Alternatively, mass market supermarkets can outsource the problem to the likes of Instacart (which uses gig workers) leveraging grocers’ existing store networks. There is no need to carry short term losses or take investment risk under this option.

In addition, Instacart can provide faster delivery than when using Ocado’s Technology. Although Instacart might cost the end consumer more, such customers prioritise convenience over price and Instacart provides the greatest convenience.

In my view, it is telling that Ocado Retail partners with Marks and Spencer and operates at the premium end of the market — online delivery cannot compete with traditional supermarkets on cost.

Of course, online versus in store is not a like-for-like comparison. But if you are motivated to save a few pounds on your weekly shop at a supermarket, then I guess you are unlikely to be willing to pay a surplus to save a small amount of time getting it delivered to your home.

Mass market grocers have a predominantly cost conscious customer base that likely do not fully appreciate the convenience that Ocado offers. Meanwhile, the grocers themselves have to take additional risk and cost when partnering with Ocado when they could alternatively outsource the problem to the likes of Instacart.

Ocado’s technology customers also do not want to become totally dependent on Ocado either. This might explain why Kroger has taken a hybrid approach to its e-commerce business utilising both in-store and CFCs. This is a more benign possible explanation for the seeming lack of enthusiasm for Ocado’s solutions.

It may just be that it has taken longer than expected for online to reach scale, but that it will eventually reach a tipping point. If and when it does, Ocado’s partners might commit to new CFCs restoring growth in the technology business.

Whatever the case, Ocado’s technology does not need to become globally dominant for the current share price to offer value. Cost cutting and already signed contracts should be enough to get it to cash flow positive. And like Accesso, Ocado should be able to leverage AI to improve R&D productivity. Management is promising to reduce these costs to 20% of technology revenue in the next couple of years.

A major risk is that Kroger walks away. Each CFC has a 10 year lease and the overall relationship has just reached seven years. The latest CFC was opened in 2023, and in 2024 Kroger ordered a variety of new automation technologies for their existing network. Therefore, it is not likely that Ocado Technology will suffer from a sudden crash in revenue in the event of losing Kroger which at least makes this outcome manageable.

Further, although Kroger is a particularly large customer, there are 12 other partners spanning the world. This diversifies partner execution and contract expiry risks and so it seems to me that the Technology division holds significant value regardless of Kroger.

Even if we assume that the technology business is worthless, the retail and logistics arms support half of Ocado’s market capitalisation (after borrowings) curtailing the downside. Nevertheless, substantial debt and currently negative cash flows do make Ocado a more risky proposition compared to Accesso with share dilution a real possibility.

The Agnelli family (founders of Fiat) have recently been acquiring stock on market and now control more than 13% of the group. They first disclosed a 5% stake in 2013 during a period of speculation regarding an Amazon takeover.

Today, the market is very pessimistic about Ocado and I think the shares are as irrationally priced as they were in the other direction back in 2021. However, I would need to see more evidence of the technology working for partners to want to own the stock in any size.

My token position should ensure that I remain vigilant to future developments. I could be wrong about online delivery economics or things could change, for example, with the commercialisation of self-driving technology. If Ocado’s tech returns to favour, then the stock price reaction could be dramatic.